If you’ve ever read a well-written murder mystery, the chances are you’ve also entertained the idea of writing one.

But how exactly do you go about it? What should you be keeping in mind as you plot your own murder mystery?

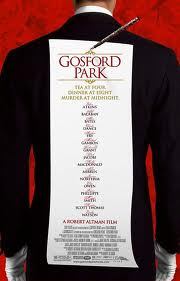

Gosford Park is a murder mystery artfully written for the screen, which garnered 7 Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay.

The movie did indeed take home a little golden statue for a screenplay written directly for the screen, beating out Amelie, Memento, and Monster’s Ball, so it’s clear there are a number of murder mystery tips to be gleaned by studying the movie.

Below are some of the ones I found:

Murder Mystery Tip #1: Even if there weren’t a murder, there should still be a story

The plot of your movie is going to revolve around the murder–or murders–committed and solving the mystery of who perpetrated the crime.

But let’s pretend no murder was committed. Would you still have a story? Would there still be undercurrents of tension between your characters? Do they still face dilemmas and demons?

Without a murder, the lives of your characters should be at least mildly interesting to an audience. With the addition of a crime, your story becomes gripping, something they must watch and/or read till the very end, when the solution is revealed.

In Gosford Park, the murder occurs eighty minutes into the movie! That may be pushing it a bit, but nevertheless, it worked. That’s because there were still several incidents which would pique an audience’s curiosity, even if the incidents didn’t have the captivating power of a full fledged mystery.

Here are a few: Freddie and Mabel Nesbitt arguing about Isobel as they walk down the grand stairway of Gosford Manor. Then Freddie pressures Isobel about something, we don’t know what. We also see the man of the house, William McCordle, flirting big time with his sister-in-law. That’s a no-no, Bill!

Mixed into all that is feisty grand dame Lady Trentham and actor/composer Ivor Novello. She interjects biting commentary into each scene she’s in, while he infuses his scenes with old school Hollywood glamor.

You’d still be interested in this world, even if the movie turned out to be a period piece along the lines of Fellowes’s other highly successful creation, and one of my favorite shows, Downton Abbey.

(Fellowes is also the author of the slow-burning modern thriller, The Tourist. You can find my analysis of that movie at Screenplay vs Film: 8 Screenwriting Tips from the Tourist.)

The beauty of this system is that all of these undercurrents–between Freddie, Mabel & Isobel; Bill McCordle and his sister-in-law; and Lady Trentham and McCordle’s purse strings–play a major role in creating suspects and establishing motives.

By creating mini-dramas involving each character, you accomplish two goals at once: you’ve hooked the audience and you’ve laid the groundwork for the sleuth’s investigation.

When you’re plotting out your murder mystery, ask yourself: if I removed the murder from the plot, would my screenplay still be interesting? Then you know you’ve got a solid beginning to your murder mystery.

Murder Mystery Tip #2: Cut back and forth between two worlds

Cutting away from a scene at a pivotal moment is a time-old technique to create suspense and to keep a reader turning your screenplay pages.

In novels, writers using the 3rd person point of view will cut between the actions of the detective and the actions of the killer. In contained thrillers, oftentimes, a few characters will get separated from the main group, and the movie will cut back and forth between both…especially when one faction finds themselves in major peril.

In Gosford Park, Fellowes uses this technique in a slightly different way. Instead of switching the point of view from the detective to the murderer, he switches between the points of view of the upper class and the working class.

Lady Sylvia McCordle, mistress of Gosford Park, leads a rich, but bored life…and if we had to watch her continuously throughout the movie, we would be bored too.

Anthony, married to Lady Sylvia’s sister, is facing hard financial times and is quite desperate for Bill McCordle to invest in his venture in the Sudan.

While the audience can sympathize with Anthony, they can’t watch his groveling for two hours. By switching from the privileged world of the aristocracy to the world of their servants, Fellowes skillfully keeps the audience’s attention engaged as story events unfold.

When you’re writing your own murder mystery, experiment with POV, and see how switching between different points of view can increase the level of suspense in your screenplay.

Be careful though. Your transitions can’t be choppy and helter-skelter. Even if you cut away abruptly from a scene, it should make sense.

Murder Mystery Tip #3: Plant clues openly, but in the background

Clues to unraveling your mystery should be made known to both the detective–and the audience–otherwise the audience will feel cheated at the end.

At the same time, you can’t plant clues so openly that everyone can figure out the solution to your murder mystery by the midpoint of your story. There again, they’ll feel cheated.

So how should you present clues that would lead the detective and the audience to the murderer?

Combine their presentation with something else, so your clue registers as “background information” to your audience. This way, they’ll have all the information they need to solve the mystery, but they won’t recognize how important the information is.

Lord Stockbridge’s valet, Mr Parker, played by Clive Owen, is an orphan. As a matter of fact, his mother was a worker in one of McCordle’s factories, whom, he believed, died. These bits of information are crucial to solving the mystery, but when they were presented, the audience’s attention was caught up in other affairs.

The first time Mr Parker’s parentage is brought to our attention, the servants are sitting down to dinner (and seating is assigned based on their master’s rank). Denton, Mr Weissman’s valet, inquires if the servants went into service because their parents were servants.

In the scene, we’re more focused on Denton’s ignorance as the butler gently mocks him than we are in Parker’s answer. Despite being the lone orphan, his response doesn’t draw undue attention to itself as other servants describe their family background.

Later, in their shared quarters, Denton, spotting a photo of a woman on Parker’s nightstand, asks him about his mother. Here we learn that she worked in a factory, gave birth to him, and then died.

Although this information is vital, the emotional valence in the scene is concentrated in the dynamic between Denton and Parker, and the way Parker puts the forward Denton in his place. Parker’s mother’s occupation become background information as Parker tells Denton to butt out.

Murder Mystery Tip #4: Gossip can substitute for an interrogation

In order to solve your mystery, whichever character is playing sleuth has to gather information from all parties, whether they be suspects, witnesses, relatives and associates of the victim, etc. But it would be very boring if the sleuth always learns new information by interrogating key players.

You can add a little variety to the necessary interviews by changing their location. The detective can interrogate major players at the scene of the crime, at the police station, or at places which feature prominently in the victim’s life.

But to really engage a reader, every scene in Act Two can’t be a variation of the detective playing Q & A. Spice it up and reveal essential information to your audience through gossipy conversations between your characters.

Gossip can be a very powerful medium of revealing information. Look at how much information is revealed through servant’s gossip in Gosford Park.

The fact that Lady Sylvia and her sister cut cards to determine who would marry Bill McCordle is a juicy tidbit bandied about by Elsie, Mary, and Lady Trentham, just to name a few. This little bit of gossip provides a motive for Sylvia to off her husband out of jealousy and revenge.

Everybody gossips about Anthony’s poor state of financial affairs. McCordle’s refusal to join Anthony in his Sudanese scheme also adds another motive to the mix, and we do in fact *spoiler alert* discover that Anthony unsuccessfully attempted to murder Bill. Elsie and Mary’s gossip about Freddie reveals he might have murdered McCordle out of disappointment, while their gossip about Lady Trentham reveals she could have killed the old codger to preserve her allowance.

In Gosford Park, gossip was especially important because the detective character, Inspector Thompson, doesn’t appear until much later in the movie. Even without his bumbling interrogations, the audience has a clear idea of the myriad party guests who would want Bill McCordle dead, and can try to unravel “whodunnit” without relying on the detective.

Murder Mystery Tip #5: Character is your foundation, not the plot

In the article Top 10 Rules for Mystery Writing, author Ginny Wiehardt’s first rule states that “in mystery writing, plot is everything. Because readers are playing a kind of game when they read a detective novel, plot has to come first, above everything else.” I heartily disagree. While I believe that plot is important, I think that character is even more important.

When you’re writing your own murder mystery, it’s easy to get lost in plotting–figuring out the precise sequencing of events, and the ways in which the murderer covered his tracks. Many hours will be spent deciding how to interweave real evidence with red herrings and false clues. (For a clear explanation of each, read Sandra Parshall’s article entitled Clues Drive the Mystery Plot.)

But as you’re trying to put all the pieces together in a way that makes sense but still maintains the mystery until the very end, don’t lose sight of the importance of character.

The only interesting thing about your detective character can’t only be that he’s the one investigating the mystery. We should care about him in his own right. He should have conflict in his person and/or professional life which makes his story worthy of following.

The same applies to the victim. You can come up with several diabolical methods of murder and even more red herrings to put the audience off the scent of the true culprit. But if the audience doesn’t care about the victim or the effect his death has on other people, then they might not be interesting in solving the mystery, however craftily it’s constructed.

When you write a mystery, you are in a sense, asking people to follow you down a few wild goose chases as your detective follows erroneous leads and hunts an innocent suspect.

Your audience can tire of all of this if they don’t have an emotional investment in the detective, the victim, the murderer and/or the people whose lives are affected by the crime.

Final thoughts

If you want to advance your murder mystery writing skills, read as many books or watch as many movies in the genre as you can. Read the novels and watch the classics the first time for pleasure. Then read/watch them again, deconstructing the author’s or screenwriter’s technique…

One last comment: there are a lot of great mystery writers…and many more hopefuls channeling their inner Agatha Christie. The way to make your mystery different is not by creating outlandish criminals or crimes, but by infusing your story with your own voice. That is what will separate your mystery from the others in this crowded genre.

Good luck!