Deus ex machina.

It’s a story killer, that’s for sure.

As the website Literary Devices points out, deus ex machina “is viewed as a sign of an ill-structured plot.”

So if deus ex machina has crept into your screenplay or novel, you’ll want to get rid of it ASAP.

In this writing article, we’ll talk about three easy ways to do that (with examples from popular movies and novels).

But first let’s set the context:

You’ve reached the end, or Act Three, of your story.

Everything’s lined up like dominoes.

After experiencing a major setback at the “all is lost” moment at the end of Act Two, your protagonist has rallied.

He (or she) squares off against the central antagonist.

There’s a moment when it seems like your protagonist has lost everything (again). But it’s merely a false defeat. At the last second, your protagonist emerges victorious.

He gets the girl. She saves the world. They catch the criminal.

Your readers will want to clap you on the back for creating such a gripping ending, right?

Maybe.

Maybe not.

It depends (among other things) on how your protagonist was able to extricate himself from:

- the “all is lost” moment at the end of Act Two

- the false defeat within the climax itself

These are two places where writers (in any genre) are likely to resort to deus ex machina.

Watch this YouTube video from Fandor to see examples of deus ex machina in popular films:

What is deus ex machina exactly?

According to Wikipedia, deus ex machina is:

A plot device whereby a seemingly unsolvable problem in a story is suddenly and abruptly resolved by an unexpected and seemingly unlikely occurrence.

A Latin term, deus ex machina translates to mean “god from a machine.”

As the YouTube channel Fandor explains:

It refers to a mechanical device that the Greeks would use to lower actors playing gods onto the stage. These gods often served as a plot device to help the characters out of a sticky situation.

Apparently, deus ex machina worked like gangbusters back then. Audiences in ancient times ate it up.

But modern audiences—the people you’re writing for?

It doesn’t go over too well.

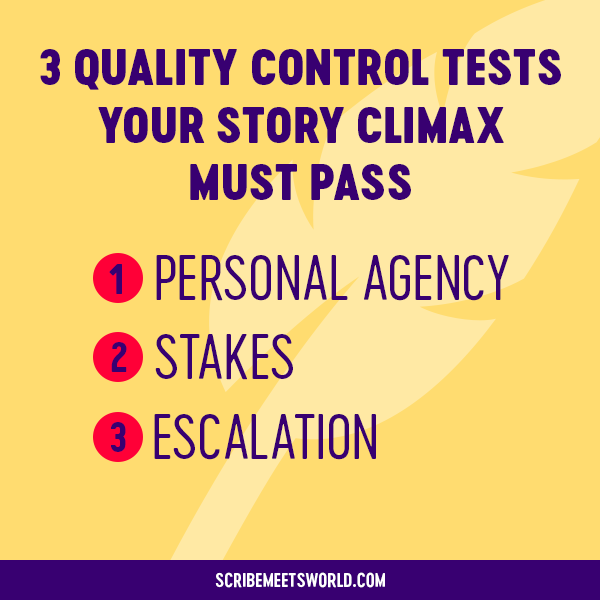

To zoom in onto the story climax—for it to be successful, it needs to pass three quality control tests:

- personal agency

- stakes

- escalation

When you resort to deus ex machina, your climax will fail the first test (personal agency).

That’s because with deus ex machina, your protagonist doesn’t have to solve his problem through his own skill and ingenuity.

Instead, a convenient solution will fall into his lap right when he needs it.

This makes him appear passive—and his eventual victory, contrived.

Basically, it turns your story ending into a big letdown…and gives readers a major reason to gripe about your screenplay or novel.

This is how Literautas describes why deus ex machina is bad:

Nothing is more frustrating than realizing the author has taken a shortcut to solve one [of] the conflicts in the story.

And here’s The Script Lab’s take on the failings of deus ex machina: “It insults the intelligence of the reader or the audience. The result is almost always disastrous.”

I’m 100% certain that you don’t want to frustrate your readers or insult their intelligence, which means you’re probably wondering…

How Do You Avoid Deus Ex Machina?

Once you’ve realized that you’ve used deus ex machina in your novel or script, you’ll want to fix it right away.

Although you may be tempted, don’t use a copout solution.

Don’t tone down the “all is lost” moment or the false defeat and make them less of a predicament so that your protagonist could find a way out with a paper bag over his head.

This is a bad idea because it’ll mess up the structure of your screenplay or novel.

When the “all is lost” moment and the false defeat are dire, you’ll take audience emotion to an extreme low. Which means, when you extricate your protagonist from these awful situations, you’ll bring audience emotion to an extreme high.

As Chris Vogler explains it in The Writer’s Journey:

The more their emotion rebounds, the more audiences will love your story.

Now can you see, scribe, why toning down the “all is lost” moment and the false defeat isn’t a great fix?

When you tone them down, there’s not much of a rebound. There’s not much of an up-and-down rhythm.

The emotional experience of audiences won’t be as intense, and they won’t be as entranced with your screenplay or novel.

Bummer.

By the way, if you want to create the kind of emotional intensity that keeps readers glued to your pages, you need to master both structure and stakes. Below are some resources to help you with that:

- My online course Smarter Story Structure

- The writing guides in the Story Structure Essentials series

- My writing guide Story Stakes (which one Amazon reviewer said should be a “must-have in your top 10 books on writing”)

Let’s return to the topic at hand: rescuing your protagonist at the climax without resorting to deus ex machina.

You know that your protagonist has to be in deep trouble—the deeper, the better. To get him out of trouble, he’ll need a solution.

For the reasons discussed above, you can’t provide him one through deus ex machina. So what can you do?

3 Easy Ways to Stop Deus Ex Machina from Wrecking Your Novel or Screenplay

Your protagonist is in a tight spot. How to get him out of it?

You can provide him with a solution right when he needs it most—just as long as you set it up beforehand.

This way, it doesn’t seem contrived and convenient.

This way, it looks like your protagonist is intelligent and savvy, taking advantage of the resources at his disposal.

(Or, if he’s doing a complete about-face—in a romance, for instance, a committed bachelor might decide he really does want to be with the heroine—it looks like his change of heart was natural and not dished out because you reached the end and needed to wrap things up.)

This way, your protagonist can still retain his personal agency (helping you pass the first quality control test).

This way, there’s no more deus ex machina.

To set up your protagonist’s solution, there are mainly three different approaches that you can use. Although all are based on the principle of pre-establishment, they differ in the effort required to implement them.

Here are the three approaches:

- Setting as setup

- Previous scene(s) as setup

- Subplot as setup

Let’s take a closer look at each option, and see how they were successfully used in popular movies and novels.

Deus Ex Machina Fix #1: Use setting as setup

I gotta warn you.

This is a simple and effective way to set up your protagonist’s solution and extricate him from a tight situation. But it’s not very thrilling.

Basically, all you have to do is introduce your protagonist’s solution when you first describe the setting of the “all is lost” moment (if that’s the tight situation) or the setting of the climax (if the false defeat is the tight situation).

To see how easy it is to use this deus ex machina fix, let’s see it in action…

Example of Using Setting As Setup to Prevent Deus Ex Machina

At the end of Michael Connelly’s detective novel The Crossing, Harry Bosch visits a crucial witness at the witness’s office (the witness is a physician). In the middle of his interrogation, Bosch realizes the bad guys (two corrupt cops) are coming for them.

Chapter 45 ends with Bosch cornered and vulnerable:

He knocked a fist on the underside of the desktop and felt and heard wood. The double layer of wood and metal might actually stop bullets— if he was lucky.

He squatted down further behind the blind and pointed his Glock at the door. He had brought the gun as part of the show to trick Schubert [the witness] into believing he was a cop. Now it might be the only thing that kept them alive. The gun was maxed with thirteen rounds in the magazine and one in the chamber. He hoped it would be enough.

He heard a slight metallic sound from the far side of the room and knew Ellis and Long [the bad guys] were outside the door and trying the knob. They were about to come in. Bosch realized at that very moment that he was in the wrong spot. He was positioned dead center in the room exactly where they would expect him to be.

In chapter 46, Bosch extricates himself from this dicey predicament and gains the advantage:

Ellis turned and saw Bosch moving laterally out from behind a folding partition that split the room. He had a gun up and opened fire as Ellis realized the overturned desk had been a decoy and Bosch had the superior position.

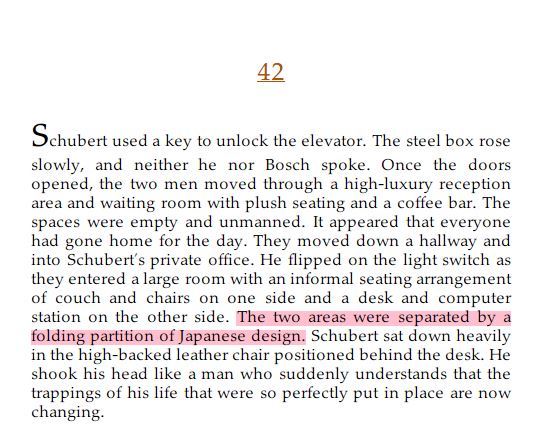

The presence of the folding partition saves Bosch’s life. It would seem mighty convenient if it weren’t set up beforehand, when the witness’s office is first described back in chapter 42. You can read the text of the setup in the screenshot of the novel, below (it’s highlighted in pinky-red):

This setup in Chapter 42 of The Crossing prevents deus ex machina in Chapter 46.

Deus Ex Machina Fix #2: Use previous scene(s) as setup

This is probably the option writers use the most often to prevent deus ex machina.

You just plant the protagonist’s solution in a previous scene (this is the setup). It will be paid off later on, when the protagonist uses the solution to extricate himself at the “all is lost” moment or at the false defeat.

If you handle the setup well, audiences will praise your cleverness as a writer.

Oftentimes, for this method to be successful, it’s important to mask the setup so it doesn’t register as such.

Because, if audiences can call it from a mile away, your story won’t be very entertaining (even though you shielded yourself from accusations of deus ex machina).

Think of it like the scene in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone where Ron Weasley encounters a three-headed dog.

When Hermione asks him if he noticed what the dog was standing on, he replies indignantly, “I wasn’t looking at its feet! I was a bit preoccupied with its heads!”

That’s how you want to embed the initial setup.

Make your readers preoccupied by something else (the three-headed dog) so that they’re not focused on the setup itself (the trapdoor at the dog’s feet).

Incidentally, this approach is also a great way to mask your clues if you’re writing a murder mystery.

The examples in this section should give you a good idea of what to aim for, so let’s take a look at those now. (By the way, we’re not yet done with Harry Potter!)

Examples of Using Previous Scene(s) As Setup to Prevent Deus Ex Machina

As part of the “all is lost” moment in the film adaptation of the Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, Frodo is speared by a cave troll in the Mines of Moria.

Frodo miraculously survives—thanks to a shirt of mithril, which is the equivalent of a Kevlar vest.

Now, if Frodo were an FBI agent wearing a bulletproof vest in an action movie, no setup would be required. Its presence wouldn’t raise any eyebrows.

But the same doesn’t hold true for mithril—something audiences are not familiar with. It has to be set up in advance.

This is how the film handles the setup: the shirt is given to Frodo by his Uncle Bilbo right after the Fellowship has been formed.

Although audiences will take note of the mithril due to its beauty, they’re unlikely to detect that it’s a setup.

That’s because their focus is quickly diverted from the shirt when the Ring of Power exerts its influence on Bilbo, temporarily twisting his features into ugliness. If you’re looking for ways to camouflage your setup, that’s a good tactic to study.

Watch it now:

In the special extended DVD edition of The Fellowship, the film actually reminds audiences about the mithril shirt after the Fellowship enters the Mines of Moria.

Watch the clip now:

Sometimes, such reminders are necessary (especially if your story is epically long). But you have to be careful with them, because if you draw too much attention to your setup, then audiences will be able to predict how you’re going to use it, which’ll diminish your story’s entertainment value.

Psst: Are you writing in the fantasy genre? Do you want to improve your plotting skills? Then check out this article on the structure of The Fellowship of the Ring.

Here’s another example of setup, this time from a rom-com: the film adaptation of Crazy Rich Asians.

At the very end of the movie, after Rachel has broken up with Nick because she knows his family will exile him if he marries her, Nick boards Rachel’s plane to fly back to New York with her.

She doesn’t want to see him. “Please don’t make this harder than it already is.”

Ignoring her protests, he gets down on one knee—right in the middle of the plane’s aisle. “Wherever you are in the world—that’s where I belong,” he says.

She responds to his romantic gesture with a “But…”

It’s clear she’s not going to say yes to his forthcoming proposal.

This is Nick’s false defeat. It looks like he and Rachel will never end up together.

But then he pops open a jewelry box, revealing a stunning emerald engagement ring.

His mother’s own engagement ring.

In that instant, audiences (and Rachel) realize that Nick’s family members have changed their minds. They do approve of her; they will accept Nick’s marriage to her.

With that obstacle cleared, Rachel is free to say yes…and Nick is extricated from his false defeat.

However, for Rachel’s acceptance to feel logical—and not like a deus ex machina—and for audiences to understand the implications of the ring, its backstory has to be set up beforehand.

The film does this in a scene where Rachel makes dumplings with Nick’s family. When Rachel admires Nick’s mother’s engagement ring, Nick’s mother (Eleanor) says Nick’s father had it specially made for her when he proposed.

You can watch that clip here:

A little while later, it’s revealed that Nick’s father had to get the ring made because Nick’s grandmother wouldn’t give him the family ring. She didn’t think Eleanor was good enough for her son (which is surprising, given the power Eleanor currently wields in the family).

Clearly, since Eleanor gave her stunning engagement ring to Nick, she has, at long last, been convinced that Rachel is good enough for him—paving the way for Nick’s proposal to yield the sought-after yes.

I really like the way this setup was used at the ending of the film because it negated the need for Nick to make explanations. Due to the setup, audiences could piece everything together for themselves—which tends to make their experience extra-satisfying.

To quote Billy Wilder, who was quoting Ernst Lubitsch:

Let the audience add up two plus two. They’ll love you forever.

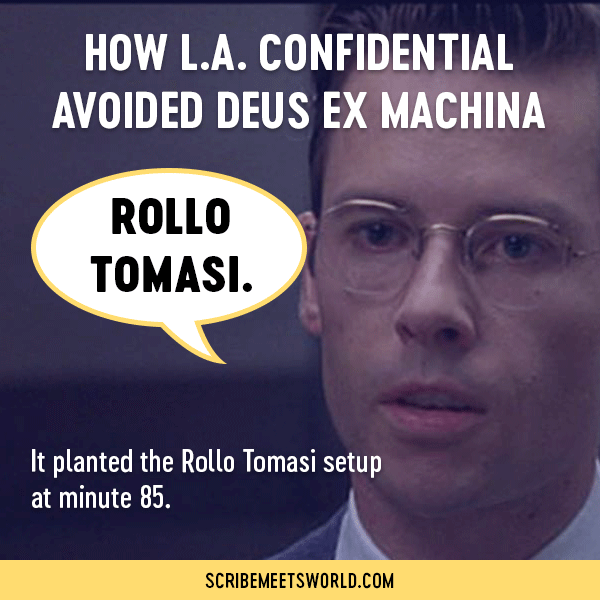

Setup was used similarly—to great effect—in the crime drama L.A. Confidential. In fact, this is one of my favorite setup examples, ever.

Vincennes has uncovered a clue that’s key to unraveling the Nite Owl murders. However, at the “all is lost” moment, he is shot dead, taking this knowledge with him.

Watch the scene now (note: this clip contains violence):

However, Vincennes manages to pass on this knowledge to his colleague, Exley, from beyond the grave. How?

Through his last words to the police chief: “Rollo Tomasi.”

When the police chief asks Exley about this name, Exley instantly realizes what Vincennes’s clue (and death) signify—the police chief is corrupt.

Exley was able to draw this conclusion due to setup in a previous scene where he told Vincennes an anecdote about his dad who, while off-duty, was killed by a purse snatcher. The cops investigating the case didn’t even know the thief’s name, so Exley gave him a fictitious one: Rollo Tomasi.

In the scene, Exley opens up to Vincennes and relates this anecdote to convince Vincennes to help him achieve justice. Because audiences think the anecdote has served its purpose, they’re unlikely to suspect that it will be used again later on as an extrication device.

Very clever. No wonder the film, co-written by screenwriter Brian Hegeland and director Curtis Hanson, won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay!

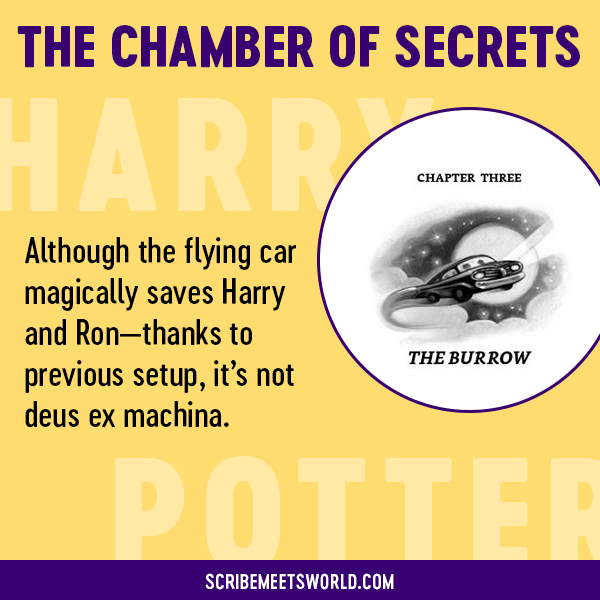

For our last example of using a previous scene as setup, let’s examine the novel Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. (Told ya Harry would be back!)

In chapter 15, Harry and Ron are about to be attacked by a horde of ravenous spiders in the Forbidden Forest. Fortunately, they’re rescued by a flying car (belonging to Ron’s dad) that whisks them away.

The arrival of the car would be a complete deus ex machina without the setup, which actually comes in multiple parts.

- Chapter 3: The flying car is first introduced to readers (it smuggles Harry out of the Dursley residence).

- Chapter 5: After transporting Harry and Ron to Hogwarts, the car is attacked by the Whomping Willow. It ejects the boys and disappears into the darkness.

- Chapter 15: The boys spot the car in the woods right before they are captured by spiders.

For reference, here’s the text regarding the setup from Chapter 5:

“Reverse!” Harry yelled, and the car shot backward; the tree was still trying to hit them; they could hear its roots creaking as it almost ripped itself up, lashing out at them as they sped out of reach.

“That,” panted Ron, “was close. Well done, car —”

The car, however, had reached the end of its tether. With two sharp clunks, the doors flew open and Harry felt his seat tip sideways: Next thing he knew he was sprawled on the damp ground. Loud thuds told him that the car was ejecting their luggage from the trunk; Hedwig’s cage flew through the air and burst open; she rose out of it with an angry screech and sped off toward the castle without a backward look. Then, dented, scratched, and steaming, the car rumbled off into the darkness, its rear lights blazing angrily.

“Come back!” Ron yelled after it, brandishing his broken wand. “Dad’ll kill me!”

But the car disappeared from view with one last snort from its exhaust.

Notice that much of the setup was embedded at the very beginning of the novel. The early positioning acts as natural camouflage. Readers will be too busy getting acclimated to your story world to detect possible setups.

So if you’re stuck wondering, Where to put my setup so it’s not obvious? try planting it at the beginning of your story, perhaps:

- when you introduce your protagonist

- during objections lobbied against the plan necessitated by the inciting incident (a technique I describe in more detail in my writing guide Inciting Incident)

Deus Ex Machina Fix #3: Use a subplot as setup

A subplot is a secondary story that’s subordinate to the main plot.

(Sometimes, a subplot is referred to as the B-story, while the main plot is referred to as the A-story.)

Generally speaking, when you use a subplot as setup, a character from the subplot will provide crucial assistance to the protagonist after the “all is lost” moment or during the climax.

Notice that when a subplot character helps your protagonist to (a) participate in or (b) win at the climax, your story will follow the golden rule of subplots which is this:

The subplot should intersect with the main plot.

Subplots are quite versatile. You can use the same subplot for multiple purposes. What am I getting at?

Simply this: you may find that your subplot does more than avoid deus ex machina. It may also add texture to your plot or—even better—grace your story with heart.

Examples of Using Subplot As Setup to Prevent Deus Ex Machina

Sometimes, the “all is lost” moment or false defeat involves a rift—and the protagonist is too full of pride to repair it. Or, in another scenario, he’s too afraid of failure to get back in the game.

However, these things need to happen for the story to come to a close.

If the protagonist just changed his mind all of a sudden, his behavior might come across as deus ex machina. But this can be prevented if a subplot character (who’s been part of the story all along) prods the protagonist to set aside his pride or overcome his fear.

You can see examples of this in both Jasmine Guillory’s romance novel Royal Holiday and the Oscar-nominated raunchy comedy Bridesmaids.

In Royal Holiday, the heroine has recently told the hero (via postcard) that she’s fallen in love with him. Gun-shy about commitment (he hasn’t dated anyone seriously since his divorce) and not sure how to handle the logistics (she lives in the US; he lives in the UK—in fact, he works for the queen), he hasn’t responded back to her.

It appears like he never will—until the end of chapter 17, when a subplot character (the hero’s nephew) talks some sense into the hero and galvanizes him into taking action.

“You’re right: it’s none of my business,” Miles [the nephew] said out of the blue. “But…you’ve said a lot lately about how I should have a baseline of success and respect from the world before following my dreams. But you have that! People respect you more than anyone I know, and instead of taking advantage of that now, it seems like the rest of your life is standing in your own way.” He shrugged. “I just…I really liked her.”

Malcolm [the hero] sighed.

“Yeah. Me too.”

But that was a lie. He knew it was a lot more than that. He just had no idea what to do about it. It all seemed impossible. Too hard, too risky, too complicated. And it might be useless—what if he tried, and it didn’t work out between them, and they’d both sacrificed for no reason? What if she was so angry at him for ignoring her for weeks that she’d realized he wasn’t the person she thought he was?

But what if it was all worth it?

In Bridesmaids, after Annie has lost her job, apartment, & best friend and given up on everything, Megan literally browbeats Annie into getting back into the game of life.

Here’s the clip (note: this clip contains cussing):

Because the nephew in Royal Holiday and Megan in Bridesmaids are subplot characters, they pop up throughout the story. Rather than listing every occurrence where they appear before they’re used to extricate the protagonist, let’s focus on when they’re first introduced.

In Royal Holiday, readers get a solid introduction to the hero’s nephew in chapter 2, when the hero gives the heroine a tour of his office. You can read the text of that introduction in the screenshot of the novel, below:

An introduction to the hero’s nephew, a subplot character used to avoid deus ex machina in Royal Holiday

In Bridesmaids, audiences first meet Megan at Lillian’s engagement party. Here’s a clip of that introduction scene (Megan is introduced at 0:52—note that this clip contains cussing).

Without going into details, I’d like to point out that these subplots are used for other purposes besides preventing deus ex machina, namely:

- to create conflict between the hero and heroine (Royal Holiday)

- to 10x the humor (Bridesmaids)

One of my favorite examples of using a subplot to fix deus ex machina comes from Home Alone. Despite Kevin’s attempts to elude two bumbling burglars, they’ve managed, at the tail end of the climax, to catch him.

Using his sweater, they’ve hung him from a hook on a door.

Things look very bad for Kevin.

Suddenly, though, the burglars are knocked out by a shovel—wielded by a subplot character, Old Man Marley.

Now, Old Man Marley and Kevin are friends. But at the beginning of the story, when Kevin’s brother fills Kevin’s head with tall tales about Old Man Marley, Kevin is terrified of him.

Gradually, Kevin changes his attitude toward his elderly neighbor, who comes to represent the spirit of Christmas. Their evolving relationship and its impact on both their lives gives the story its heart and is one reason why I love this example so much (and why the movie is such a Christmas classic).

An interesting use of subplot as setup (which works really well in a thriller) is when the subplot involves a character with ambiguous loyalty—someone about whom you’re asking questions like, Is this character in the protagonist’s corner or not? or, Will this character trust the protagonist?

At the end of the story, the subplot character will rescue the protagonist in some way. But it doesn’t feel like deus ex machina (the subplot character has been portrayed as someone who could potentially help the protagonist; that was never categorically ruled out). At the same time, it’s not quite predictable (the subplot character’s portrayal has, for the most part, leaned in the other direction).

Good examples to study include the relationship between:

- Tris and Peter in the film adaptation of Insurgent

- Doug and Melina in Total Recall (1990)

- the villain and the villain’s girlfriend in Ransom (this one is particularly well done)

A Word of Caution About Using Setups

Although setups are extremely effective at preventing deus ex machina, you have to use them carefully. Just because they are in place doesn’t mean all is well.

For one thing, you have to make sure that you haven’t undermined your protagonist’s personal agency in other ways.

Going back to Home Alone, Kevin doesn’t do anything to the burglars after Old Man Marley rescues him. So it’s really Old Man Marley who brings the main conflict to a close. In most stories, this wouldn’t cut it. It works here, though, because Kevin is only 8 years old, so we cut him some slack.

Also, setups aren’t always warranted. In some cases, they can actually detract from audience enjoyment, especially if you’re using a “sleight of hand” narrative style.

In the 2001 remake of Ocean’s Eleven, two setups in the screenplay draft were dropped in the produced version of the film, likely for this reason. If you want to examine those examples, check out this article on screenwriting tips from Ocean’s Eleven.

On the other end of the spectrum, you also want to be on the lookout for times where you included a potential setup, but didn’t exploit it as such.

At one point in the heist novel The Chase (written by Janet Evanovich and Lee Goldberg), the heroine is given a bottle opener shaped like a fancy hotel. It could’ve been an excellent extrication device to use at the climax, but as I recall, it doesn’t feature at all in the novel’s ending.

Going Further with Your Story Climax and Story Structure

After reading this article, you should have a solid grasp of how to avoid deus ex machina at the ending of your story.

But there’s more to crafting a killer climax than that.

If you’d like to learn more strategies for passing all three climax quality control tests (personal agency, stakes, and escalation), then check out my writing guide Story Climax.

If you’d like to focus exclusively on deepening your understanding of the stakes—which are crucial not only to enhancing your story climax but also to getting audiences to care about what happens in your story—then take a look at Story Stakes.

If you want to become better at all aspects of story structure (not just the climax):

- Download the Ultimate Story Structure Worksheet. (A free, 18-page worksheet that’ll help you plot your next screenplay or novel like a boss.)

- Read the writing guides in my Story Structure Essentials series. (You’ll get a “deep dive” on how to set your story up for success, say good-bye to saggy middles, and craft endings that exceed audience expectations.)

- Enroll in my online course Smarter Story Structure. (Distills years of studying why some stories are so gripping—while others are easy to walk away from—into 30 bite-sized lessons. Perfect if you want to learn how to wield story structure like a pro, in the shortest amount of time.)

Deus ex machina angel by Roberto Catarinicchia; Roller coasters by Mark Asthoff