Let me take a wild guess.

You don’t want the end of your screenplay or novel to be a letdown, do you, fellow scribe?

No, of course not.

You know the outcome of that isn’t pretty.

That’s because the climax of a story (along with the resolution) is your last chance to make a good impression on audiences.

Bungle it up, and they’re not going to rave about your screenplay or novel—even if they were keen on its beginning and middle.

You can say good-bye to word-of-mouth recommendations—and having others do the marketing for you.

I’m sure you don’t want to say good-bye to that.

Which means you’ve got to nail the climax of your story.

The resolution too, but we’re not going to talk about that key structural turning point here.

Anyway, back to the climax.

You want to make it “pop.”

To make the climax of your story so spectacular that audience members can only draw one conclusion. Gosh, this writer is an amazing storyteller. Investing time in this story was a good call.

Or, to paint it more dramatically, they’ll feel like That Guy who bought a stake in Seinfeld.

Best. Decision. Ever.

But before you worry about crafting a climax that’s epically good, you’ve got to understand the basics of the climax first.

That’s what we’ll initially focus on in this article, which is like a 101 guide to the story climax, with definitions and practical tips about this pivotal component of story structure.

More specifically, we’ll review the 5 Ws and the 1 H—

- who

- what

- where

- when

- why

- how

—as they apply to the climax of a story…although I’m going to discuss them in a different order.

By the way, much of this info comes from chapter 11 of my writing guide Story Structure for the Win. If you’re looking for a quick primer on story structure (which’ll help you write better stories—faster), you should check it out.

Okay, now let’s explore the 5 Ws and the 1 H of the story climax!

WHY is the climax of a story important?

It’s important to your protagonist because it solves his problem for good.

Yes, he does get the girl.

Yes, she does save the world.

No, they don’t catch the criminal. (Note: This is a downer. Tread carefully with that kind of climactic outcome.)

The climax of a story is important to you because…well, I already told you that 😉

The climax (along with the resolution) is your last chance to make a good impression on audiences so they equate your name with gripping stories.

WHAT is the climax of a story, exactly?

It’s the final confrontation between your protagonist and his central antagonist.

The nature of the confrontation will largely be determined by genre.

If you’d like another definition of the climax of a story, consider this one provided by Deborah Chester in The Fantasy Fiction Formula:

Climax is the ending of the story, the most intense and dangerous portion of your plot, where the protagonist and antagonist should have a showdown that resolves the situation. Even better, the climax is where the protagonist will be tested so hard that all seems lost before she’s let off the hook.

Interestingly, Chester argues that the escalating conflict your protagonist experiences during the middle of the story is actually training for “the huge ordeal of the story’s climax.”

WHO are the key players (besides the protagonist, duh)?

Although henchmen, gatekeepers, and other low-level antagonists can play a role in the climax (not to mention sidekicks and other supporting characters), the climax isn’t about them.

It’s about your protagonist’s final struggle with his central antagonist, i.e. the most powerful entity that has, repeatedly, throughout Act Two (a.k.a. the middle of a story), stood in between your protagonist and your protagonist’s goal.

Basically, the central antagonist is the person who’s given your protagonist the most grief.

Antagonists typically come in four forms:

- villains (evil bad guys)

- nemeses (as driven as villains, but not evil; think Miranda from The Devil Wears Prada or Terry Benedict from the Ocean’s Eleven remake)

- amorous opponents (my fancy term for love interests *ooh la la*)

- rivals (a special class of nemeses who compete for the same thing; e.g. the treasure, a sports trophy, a promotion, etc.)

Some writers are inclined to pile advantage after advantage onto the protagonist of their stories (usually because their protagonist is based on themselves, and the climax becomes wish fulfillment).

On the other hand, some writers pile advantage after advantage onto the antagonist (because the antagonist was the most fun character to write).

But to craft a successful story ending, you can’t cave in to either inclination.

Instead, keep your protagonist and antagonist evenly matched.

For more details on why that’s important (and how to achieve it), read this.

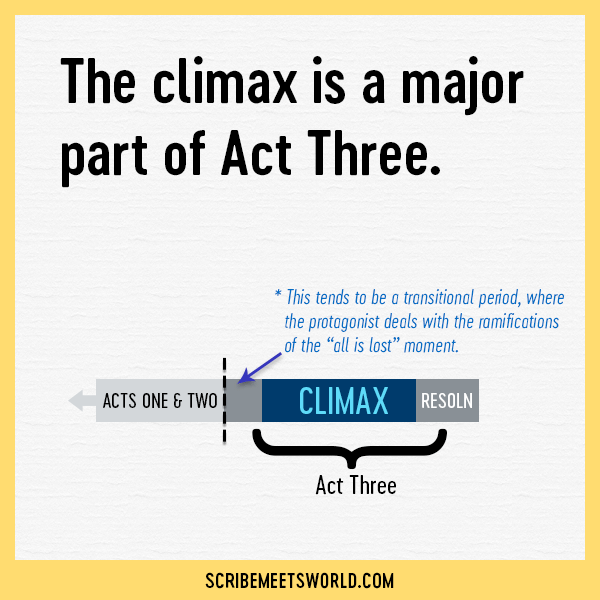

WHEN does the climax of a story occur?

It occurs during Act Three, or the end, of your story.

It comes after the period when your protagonist deals with the ramifications of the “all is lost” moment and before the resolution (when your protagonist, assuming a happy ending, gets to enjoy the fruits of his labor).

Let’s focus on the climax’s late positioning for a second. Do you see what this means? It means that the climax has greater burdens to bear than the beginning or middle of your story.

See, a jaw-dropping climax can salvage a beginning or middle that’s so-so.

Alas, the reverse isn’t true.

Even if audiences are impressed by a memorable beginning or middle (loaded with twists and turns), their enthusiasm is going to evaporate as they sit through a climax that’s dull or wimpy.

Basically, in this scenario, you’ve built up audiences’ expectations, made them feel like they were in for a really good ride…only to dash their hopes at the last second.

This offense is a lot less forgivable than starting off slowly, only to pull off a miracle and astound audiences at the end.

Fortunately, there are some great tools at your disposal to ensure that your story climax is up to scratch—namely, the remaining W…and the lone H, i.e. where and how.

WHERE does the climax of a story take place?

What happens during the climax (and how it happens) are dictated by your:

- plot

- protagonist

- genre

But where it happens? That’s basically up for grabs.

Picking the right setting is an easy and surefire way to take your climax from drab to fab.

Choose carefully!

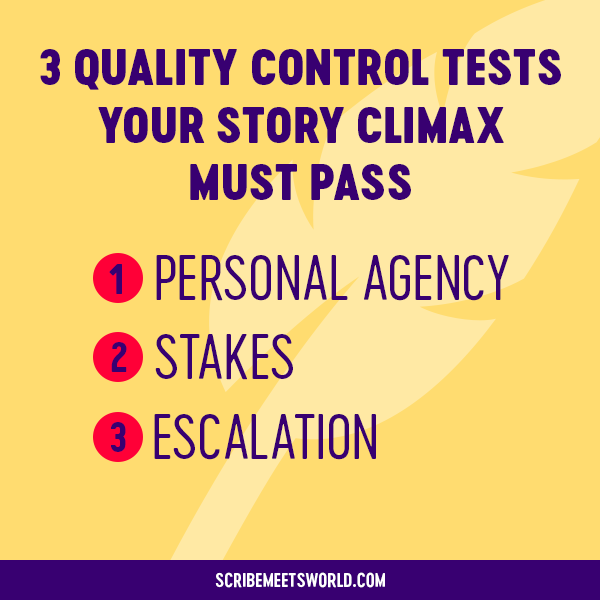

HOW do you make the climax of a story spectacular?

If you want audiences to gush about your story once they’re done with it, your story climax can’t be overshadowed by your beginning and middle.

To avoid that career-stalling outcome, your climax must pass three quality control tests.

Let’s take a brief look at each one, in turn.

Climax Quality Control Test #1: Personal Agency

Your protagonist must solve his problem or achieve his goal through his own skill and ingenuity.

He can’t be rescued by another character because that’ll make him appear passive—and undermine your entire climax.

At the same time, your protagonist can’t hog the spotlight. Other characters should also have a chance to shine at the climax. In sum, a balance must be struck.

Just as your protagonist can’t be rescued by another character, he can’t—for the same reason (it renders him passive)—be rescued by coincidence.

As you work on refining the climax of your screenplay or novel, examine how your protagonist is able to participate in the climax in the first place—and how he wriggles out of it, at the very end.

In other words, pay attention to what happens at:

- the “all is lost” moment that ends Act Two

- the false defeat (almost like a miniature “all is lost” moment within the climax itself where it seems like your protagonist has lost everything)

These two spots are danger zones.

Why?

They’re where writers oftentimes resort to deus ex machina. That is, they hand their protagonists a convenient solution on a silver platter.

This undermines your protagonist.

It undermines your story climax.

And readers loathe it.

So, if you’re prone to using this much maligned plot device at the end of your novel or screenplay, make sure you read this article on 3 easy ways to avoid deus ex machina (with examples from popular movies and novels).

Climax Quality Control Test #2: Stakes

Okay. This is the first time I’m bringing up the stakes—the negative consequences of failure.

Although I’m only mentioning them now, please don’t make the mistake that so many writers do (it’s one I made too). Don’t underestimate their importance.

As screenwriter and Emmy-award winning producer Erik Bork observes:

Now, the beginning of a story might not work because the writer simply neglected to include any stakes at all.

The middle of a story might not work because the stakes weren’t raised.

As for the end…

…it might not work because the stakes were taken out of play prematurely.

Because, once the stakes are no longer part of the picture (i.e. once they’re brought to a place of safety), it doesn’t matter what your protagonist does. All of his hijinks will feel anticlimactic and unsatisfying.

![Image of muscular guy with text overlay: These [muscles] don’t always impress. I.e. the hijinks in the climax won’t impress without stakes.](http://scribemeetsworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Lackluster-climax-without-stakes_600px.jpg)

In short, you can’t be overly protective of your protagonist (or the stakes). Keep the stakes in a precarious position—right up until the last second.

Quick pro tip: At the climax, money (by itself) doesn’t make for great stakes.

If the climax of your screenplay or novel matters because it determines whether the bad guy will get away with millions (or whether the good guy will get the stash in the heist)…

…your climax is going to receive a lukewarm reception.

To earn audiences’ enthusiastic seal of approval, make the climax about something more. Put another set of stakes in play. (For ideas, read this.)

Climax Quality Control Test #3: Escalation

The climax should feel bigger and grander than what precedes it. (This is due to its late positioning, which we already talked about.)

Multiple elements play a role in achieving the desired effect. Let’s focus on one of them: duration.

The duration of the climax sends a message about its importance. A long climax infuses your ending with a sense of weight and momentousness, i.e. escalation.

A short climax can feel insubstantial—and hence, unsatisfying—in comparison.

Put another way:

A short climax can make audiences feel shortchanged.

So even though you’re tired, and you want to finish the darn draft already, don’t rush through your ending.

Don’t let your climax become wimpy!

Instead, take the time to build up the climax and extend its duration.

Going Further with Your Story Climax and Story Structure

After reading this article, you have a basic understanding of the climax and some solid tips on how to make it great.

However, if you’d like to dive deeper, check out my writing guide Story Climax.

It’ll give you loads more practical tips on how to pass each quality control test (personal agency, stakes, and escalation) so you can craft a climax that thrills and delights audiences…

…thus paving the way for future sales.

Maybe you’d like to expand beyond the story climax and work on improving the structure of your story as a whole.

After all, when you become a pro at story structure, you’ll not only have markers to write toward (which’ll help you write faster).

In addition, you’ll create the up-and-down rhythm that keeps audiences glued to the pages of your screenplay or novel.

If you’re looking for a quick primer on story structure, take a look at Story Structure for the Win.

You’ll find the same “to the point” advice that you found in this article—only you’ll get it for all the major structural turning points, not just the climax.

If you’d like more than a quick primer, consider enrolling in my online course Smarter Story Structure.

It distills years of studying why some stories are so gripping—while others are easy to walk away from—into 30 bite-sized lessons. It’s a good option for you if you want to learn how to wield story structure like a pro, in the shortest amount of time.

After you whizz through the lessons in the course (from the comfort and convenience of your own home), you won’t be fazed by problems like these:

- the story starts too slowly (according to a Goodreads survey, 46.4% of readers abandon novels for this reason)

- the story doesn’t get going until halfway through (this happened in almost a quarter of scripts read by a studio reader in a year)

- the middle “runs out of gas” (even John Grisham admits this is a tricky issue)

- the climax doesn’t deliver fireworks, merely sparklers

- the story is the right length…but isn’t a good read (uh-oh)

Climactic mountain peaks by Maarten Duineveld; Hello, my name is gripping by Allie;

Muscular guy by Jorge Gonzalez