Plonk!

That’s the sound of someone putting down your novel or screenplay.

Why?

Its pacing was just too sluggish at the beginning.

It got bogged down by exposition or backstory—or both.

Betcha you want to avoid that, huh?

Fortunately, you can—with the inciting incident.

I’ll explain everything after the jump. So stay with me and scroll down!

ARE YOU ON PINTEREST? Save the image below to one of your boards on Writing, Plotting, Story Structure, or Screenwriting. (When you hover over the image, a Pinterest save button will appear in the top-left corner. Click on that to save to Pinterest.)

How does this process work? How does the inciting incident prevent readers from putting down your novel or screenplay?

It all has to do with the function of the inciting incident.

One of the essential plot points in story structure, the inciting incident sets your plot in motion.

Let’s elaborate on that definition. The inciting incident is a catalyst that gets everything going, nudging your protagonist toward his journey.

Now that you know its function, can you see why the inciting incident is so valuable?

It reassures audiences.

When well timed, it tells them you’re not going to stall.

You’re not going to regale them with a bunch of backstory or other material that they don’t really need to know right now (perhaps not ever).

You’re not going to describe everything about your protagonist—except how he actually gets embroiled in the plot.

You’re not going to spend 20 pages, maybe even 50 (gasp!), on the literary equivalent of clearing your throat.

Nope.

You’re going to do what you promised. You’re going to give them the story you enticed them with (in a logline, query letter, book cover, or book description, etc.).

Moreover, you’re going to do it sooner, rather than later.

Having been thus reassured, audiences become confident about your storytelling skills. They will keep on reading your novel or screenplay instead of putting it down.

In other words, if you want the beginning of your novel or screenplay to have the kind of pacing that attracts—rather than repels—audiences, then you need to be able to identify when the first inciting incident of your story occurs.

The sooner it appears, the more quickly audiences will conclude that you know what you’re doing.

Here’s where things get tricky: a lot of events can look like an inciting incident…but not really be an inciting incident.

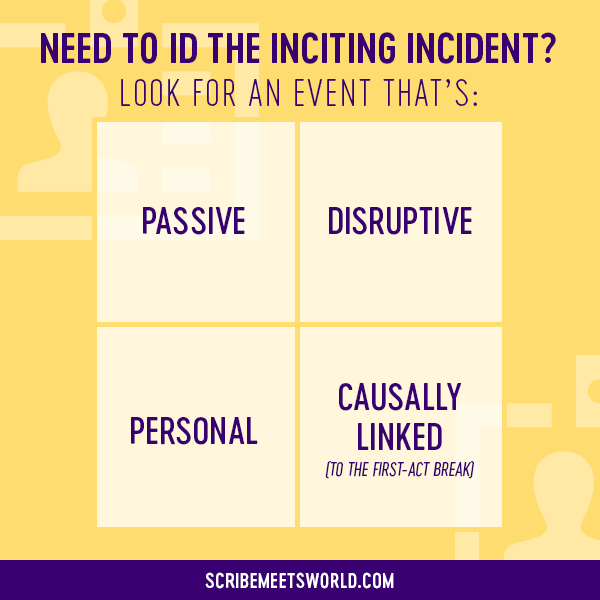

Look for the earliest plot point that fulfills all of the following four characteristics.

The inciting incident is:

- passive

- disruptive

- personal

- causally linked to the first-act break

To identify the inciting incident, look for these 4 characteristics

Want more details about each characteristic as well as examples of the inciting incident? Just keep on reading!

(After we go through the four key traits of the inciting incident—with examples—I’ll explain how to use this crucial story structure element to solve pacing problems at the beginning of a story.)

The Inciting Incident Is Passive

The inciting incident is something that happens to your protagonist.

He doesn’t orchestrate it.

Not directly.

Sure, sometimes his actions may inadvertently lead to the inciting incident, but usually, that’s not his intention.

Look at Kung Fu Panda’s Po.

Was he trying to become the next Dragon Warrior?

No.

He did everything he could to secure a spectator seat at the Dragon Warrior tournament…

- shooing customers out of his dad’s restaurant so he could stop working and attend the spectacle

- hustling up the hundreds of stairs that lead to the Jade Palace, where the tournament is taking place

- devising zany strategies to catapult himself over the palace’s walls

…but he didn’t actively pursue Warrior status.

In fact, at the film’s inciting incident, when he is selected as the next Dragon Warrior, Po is as incredulous as the other competitors, their mentor, and his adoptive father.

The Inciting Incident Jolts Your Protagonist out of His Everyday World

If the inciting incident didn’t occur, it would just be “business as usual” for your protagonist.

But, due to the inciting incident, his existence is thrown into disarray. He’ll spend the rest of your novel or screenplay trying to restore balance to his life—balance that the inciting incident threw out of whack.

This “business as usual” section usually doesn’t take up many pages.

All the same, make it interesting.

If the inciting incident didn’t happen, there should still be something going on within your protagonist’s everyday world that would warrant audience interest.

As Alex Epstein comments in Crafty Screenwriting, maybe it’s not something you’d pay money to experience, but nevertheless, it piques curiosity, however slight.

Naturally, the more curiosity you can generate, the better.

Matt Weston is a CIA agent in the spy thriller Safe House. Because his safe house is underutilized, his everyday existence is pretty vanilla. The arrival of Tobin Frost—a former agent who’s “an expert manipulator of human assets”—will change all that.

But before Frost enters the picture, there’s still stuff going on in Weston’s life. Weston is clearly lying about his job to his French girlfriend. At any minute, his lies could blow up in his face.

Weston’s also a talented guy with barely anything to do. If the inciting incident didn’t happen—if Weston was never told to prepare his safe house for Frost’s arrival, if Frost never arrived on the doorstep of Weston’s safe house—Weston could’ve done something reckless just to prove to his superiors that he’s worthy of an exciting assignment away from his pokey old safe house.

You can see something similar in Total Recall (1990). Like Matt Weston, Doug is dissatisfied with his life, especially with his job. Even if Rekall, Inc. never tempted Doug with its offer of a memory-implanted vacation that’s “cheaper, better, and safer” than the real thing—even if he never went to its headquarters, never discovered that his memories had been erased—there was a real possibility he’d do something rash, just to shake things up.

In sum, Weston and Doug’s discontent with their respective everyday worlds piques curiosity. Mild curiosity, sure—but mild curiosity is better than none at all.

For more tips on how to generate curiosity about your protagonist’s everyday world, see chapter 1 in my writing guide Inciting Incident (more details at the end of this article).

The Inciting Incident Is Personal

The inciting incident personally affects your protagonist (or someone or something that he values) in an essential way.

That is, in most cases.

There is a big exception: it’s the commission of a crime. Without this event, your murder mystery or thriller couldn’t get started. That’s why, technically speaking, it’s the inciting incident of your story.

But if you think about it, the case that results from the commission of the crime doesn’t have to be assigned to your protagonist. It could be assigned to someone else.

A colleague of your protagonist, perhaps.

Things don’t become personal for your protagonist until he’s embroiled in the plot.

Until he’s assigned the case.

For this reason, I suggest you treat:

- a non-personal crime as a facilitative, or conducive, condition

- the assignment of the case (or however your protagonist becomes personally involved in the plot) as the inciting incident

Operating on this principle should help you better understand when your story’s really getting started, and hence, puts you in a better position to evaluate the pacing and momentum of your story beginning.

Note #1: If you are writing an action movie, mystery, or thriller, you’ll definitely want to check out the bonus pacing tip at the end of this article.

Note #2: Speaking of mysteries, by and large, they end happily (i.e. the murderer is identified and apprehended). But in some circumstances, you might want to explore other options.

To learn what these options are, as well as how to pick the perfect ending for your story, read this.

The Inciting Incident Is Causally Linked to the First-Act Break

The inciting incident specifically triggers the first-act break, which is when your protagonist pursues his overall goal in earnest.

More simply, the inciting incident is the cause; the end of Act One is the effect.

What does this mean?

If you have an idea of what occurs at the first-act break of your story, you can work backward to come up with a potential inciting incident.

Here, let me walk you through how this works.

To do so, I’m going to focus on a specific type of plot (but, to be 100% clear, you can use this working-backward trick on all types of plots).

Okay, let’s dive in…

Frequently, in romances, comedies, romantic comedies, and buddy-cop stories, the protagonists become locked into their particular situation at the first-act break. (I call these plots of coerced coexistence.)

Think of when:

- An uptight FBI agent must solve the case with an unpredictable Boston cop (The Heat).

- An uptight playwright must share her home with a free-spirited media mogul (Something’s Gotta Give).

- An uptight professional ice skater must pair with an easygoing partner in order to have a shot at a gold medal (Cutting Edge; Blades of Glory).

- A monster, who’s supposed to terrify children, must come to the aid of a giggling little girl who treats him like a cuddly pet (Monsters, Inc.).

Because the first-act break and the inciting incident are causally linked, when you know that your protagonists are going to become locked together by the first-act break, you can work backward from the first-act break to derive a potential inciting incident for your story.

As an example, let’s zoom in on Something’s Gotta Give. What could cause the playwright (her name is Erica) to share her home with the mogul—despite her misgivings

What could cause this to happen?

What if the mogul unexpectedly has a heart attack—and receives medical advice to convalesce somewhere nearby?

From these circumstances (assuming Erica grants her consent), it’s easy to see how the mogul could end up in Erica’s home.

Heart attack. Voila, instant inciting incident.

Same goes for Blades of Glory. Why would two male figure skaters who (a) are accustomed to singles skating and (b) despise each other want to skate together, as a pair? What would drive them to such extremes?

Well…if they got banished from their specialty and could no longer compete as individuals, it’s easy to see how they might exploit a loophole just to stay in the game.

Banishment. Again, instant inciting incident.

As a quick side note, although Pitch Perfect 2 isn’t driven by a plot of coerced coexistence, it uses an inciting incident similar to Blades of Glory. Only, rather than men’s singles figure skating, Pitch’s heroines are banned from competing in collegiate-level a capella.

Bonus Tip: How to Solve Pacing Problems with the Inciting Incident

This article was originally inspired by a question submitted by Scribe Meets World reader Amadeo.

He wanted to know, “What is the inciting incident of Sherlock Holmes (2009)?” To answer this question, let’s look at three pieces of information:

- The plot of the film revolves around Holmes’s attempts to stop Lord Blackwood’s nefarious schemes.

- At the beginning of the film, Holmes cavorts around London in order to find a missing girl whom Lord Blackwood intends to sacrifice.

- The first event that gets Holmes entangled in this particular plot is when the girl’s parents seek him out, i.e. they assign him this case.

Here’s where it gets interesting: the third item—the film’s inciting incident—isn’t shown onscreen.

Instead, the film begins with Holmes’s reaction to this inciting incident. As a matter of fact, audiences don’t immediately know what Holmes is up to.

Six minutes transpire before Holmes explicitly states that the missing girl’s parents hired him to find her. And that’s why he’s cavorting all around London.

Notice that if this offscreen technique hadn’t been used, audiences would’ve seen the girl’s parents ask Holmes to take on the case. Audiences would’ve experienced this scene firsthand instead of hearing about it after the fact, from Holmes.

Because the offscreen technique was used, audiences were able to skip over this administrative task, which in all honesty, would have bored them.

Indeed, this is one reason why it can be advantageous to dispense with your protagonist’s everyday world and start your novel or screenplay with your protagonist’s reaction to the inciting incident.

From word one, page 1, scene one—your story is in motion.

If you’ve ever been accused of taking forever to get your story started, take the offscreen technique for a little test-drive. It’s an excellent way to quicken the pacing of your story’s opening pages.

With it, no one can claim your novel or screenplay has a sluggish start.

That said, there are some circumstances where you’re better off launching with a more leisurely beginning. (By the way, I discuss what these circumstances are in chapter 5 of my writing guide, Inciting Incident.)

Speaking of…

Learn how to start your story in the right spot

Although we covered a lot in this article, we’ve just scratched the surface with regard to the inciting incident.

There’s more to learn about how to successfully ease readers into your novel or screenplay.

With the Revised & Expanded edition of my writing guide, Inciting Incident, you’ll learn next-level techniques that’ll pull in audiences AND keep them connected to your plot & characters—all while maintaining an engaging pace.

I loved INCITING INCIDENT. It was so great that this morning I bought MIDPOINT MAGIC. My plan is to buy all the books in the Story Structure Essentials series.

In Inciting Incident, we’ll cover topics like the following:

- how much “everyday” world to include before the inciting incident—and when reducing these pages can really backfire (+ 5 tips to make your protagonist’s everyday world more interesting so audiences don’t get bored before they reach the inciting incident)

- how to time your inciting incident to catch audience attention, including how to delay it without creating a plodding beginning that irritates audiences…and also when it might be wise not to show it at all

- the secret ingredient that made Liam Neeson so appealing in Taken and Ryan Reynolds so attractive in The Proposal (it’s not what you think)

- 6 tricks to instantly make your inciting incident more memorable

- advice for handling the section of your story after the inciting incident

- what starting point you should use when you know that your current one is too rushed and you’ve gone too far ahead in the plot for your story beginning to truly satisfy audiences

- 8 approaches to ease audience members into your novel or screenplay (and why some “controversial” story beginnings might not be as bad as you believe)

- how to tell if your prologue is justified (and the simple labeling trick that may save you loads of grief)

- 7 principles for evaluating the merit of the flashforward opener

- why—if you’re tempted to throw out your exciting beginning because audiences won’t care about your characters yet—you might be operating from an erroneous assumption

- an easy fix to organically weave in exposition and avoid those “as you know” conversations that drive audiences crazy

- how to determine how many details to provide to audiences so that they can immediately understand what’s happening (but without resorting to the dreaded “info dump”)

- when to introduce your theme so that audiences will be receptive to hearing about it

- a tool that will make audiences regard slower, character-driven opening scenes with fascination instead of complaint

Buy Inciting Incident now…

…and get better at setting your story beginning at the right point today!

Download the ebook instantly or buy the paperback

(free shipping with Amazon Prime):

Fire firestick 4 by Zoutedrop

Cup of pens used to write inciting incident by Alejandro Escamilla