You are this close to writing THE END of your novel or screenplay.

All you have to do is write the resolution, i.e. depict the outcome of your story climax.

The resolution is not that long. Because it’s so short, you might not give it much thought in advance.

But that can lead to all sorts of problems.

In fact, that could undermine all the effort you put into crafting a gripping beginning and middle.

Not to mention all the effort you put into prolonging the tension at the climax.

That’s due to the resolution’s late (even later than the climax’s) positioning.

If you bungle it up, that will cast a dark cloud over everything that comes before it.

Instead of praising you for everything you did right, audiences will criticize you for ending on the wrong note.

I’ve seen Amazon reviewers dock stars from their reviews because the writer picked the wrong resolution (or, perhaps, left it out altogether!).

As award-winning sci-fi author Nancy Kress put it:

Endings carry tremendous weight with readers; if they don’t like the ending, chances are they’ll say they didn’t like the work.

ARE YOU ON PINTEREST? Save the image below to one of your boards on Writing, Plotting, Story Structure, or Screenwriting. (When you hover over the image, a Pinterest save button will appear in the top-left corner. Click on that to save to Pinterest.)

To quickly recap the preceding point: if you don’t want to sabotage your story’s chances of success, you need to pick the best, most appropriate, ending for it.

But before you send out your novel or screenplay for real-world feedback, you’ve got to write it first.

Here again, the resolution is crucial.

It tells you where your story is ultimately headed. Without knowing this destination, it’s virtually impossible to develop a cohesive, meaningful plot.

This is how screenwriter Craig Mazin, in episode 44 of the Scriptnotes podcast, explains why knowing the ending is valuable:

Frankly if you’re writing and you don’t know how the movie ends, you’re writing the wrong beginning. Because to me, the whole point of the beginning is to be somehow poetically opposite the end. That’s the point. If you don’t know what you’re opposing here, I’m not really sure how you know what you’re supposed to be writing at all.

Let’s frame Mazin’s comment within the context of writing process.

If you’re a dedicated pantser, who writes on the fly, without an outline, then the resolution might be the only major structural turning point you need to know before you start writing a draft.

If you’re a hardcore plotter, who likes to outline your story in advance, then you’ll determine not just the resolution beforehand but also all the plot points that precede it.

If you’re somewhere in between, you might generate a loose outline based on story structure. Accordingly, your outline would include the resolution, along with the inciting incident, first-act break, midpoint, etc.

But the common denominator between all of these approaches is the resolution.

It’s what you need, at the bare minimum, to start writing a draft—whether you’re a plotter or a pantser. And in the next section of this article, we’ll take a look at what your options are.

By the way, if you’re interested, here are more resources on how to create a loose outline for a novel or screenplay:

- How to Write a Script Outline (an article with advice that works for novels too, btw)

- Sizzling Story Outlines (writing guide with step-by-step instructions for screenwriters and novelists)

- Your First Screenplay (see chapter 10)

Actually, much of the info in this blog post comes from chapter 13 of my writing guide Story Structure for the Win. In it, you’ll find the same “to the point” advice that’s in this article—only you’ll get it for all the major structural turning points, not just the resolution.

And now let’s dig into how to choose the resolution of a story and end your screenplay or novel the best way…

3 Ways to End a Novel or Screenplay

When you’re figuring out what your resolution will be, you don’t need to know exactly what your protagonist will be doing during it.

Nor do you need to know how you’re going to present it (as a bookend, twist ending, etc.).

That can come later—after you’ve determined its overall nature. That’s the only thing you need to know about it before plotting or pantsing your way to a final draft.

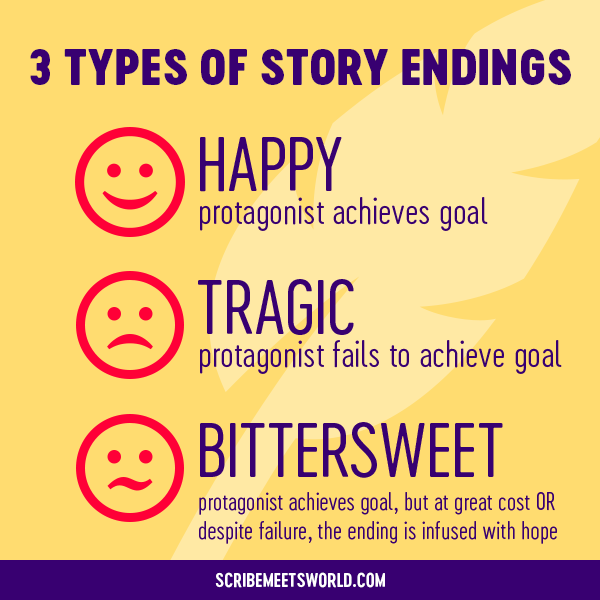

Typically, the outcome of the climax comes in three forms:

- happy (the protagonist achieves his goal)

- tragic (the protagonist fails)

- bittersweet (the protagonist achieves his goal, but at great cost OR despite the protagonist’s failure, the ending is, nevertheless, infused with hope)

How to Pick the Perfect Ending for a Novel or Screenplay in 4 Easy Steps

Okay. Now that you’re aware of your options for the resolution of a novel or screenplay…

…how do you figure out which ending is most appropriate for your story?

That’s easy. You just have to reflect on various considerations, which can be grouped together into four categories:

- genre

- meaning

- impact

- honor

By systematically reflecting on each category, you’ll have a methodical process to choose the most appropriate resolution for your story.

Let’s take a closer look at the steps in the process…

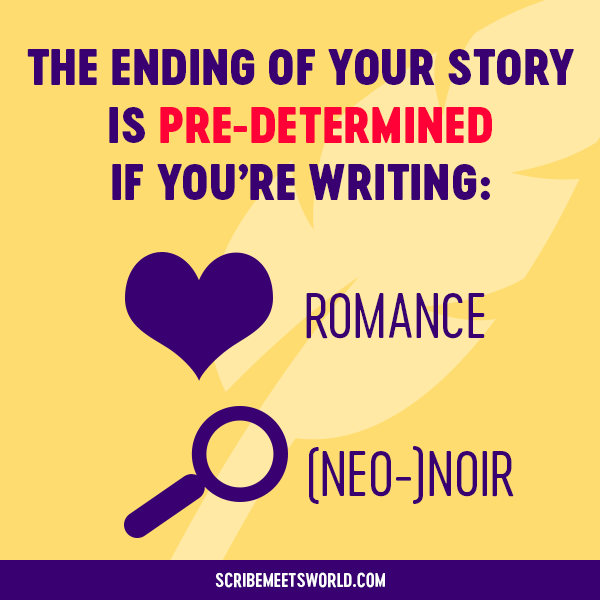

Step #1: Reflect on your story’s genre.

In some cases, genre pre-determines the ending of your novel or screenplay.

You really don’t get a say in the matter. The conventions of genre dictate your choice.

Romance is one such genre.

A happy ending is par for course. If you don’t end with an HEA (happily ever after), or perhaps with an HFN (happy for now), then you’re going to anger your audience.

Massively.

The happy ending is what they’ve been looking forward to. They’ve been waiting your whole story to reach it.

That’s why tragic and bittersweet endings don’t cut it. Using them is not a good way to make your plot feel fresh.

Here’s how Angela James, an editor for Carina Press, explains the appeal of the happy ending in a romance:

This guaranteed ending is what makes romance work. It generates comfort, satisfaction and positive feelings within readers…Kill off a protagonist, pair him or her with someone else, or leave things unfinished, and you’ll have readers who feel you’ve disrespected them and the genre. In their eyes, you may have written a love story, but you haven’t written a romance.

Which brings us to author Nicholas Sparks.

A romance plot is at the heart of all of his novels. But some of them end with a bittersweet resolution.

For example, the protagonists do not end up together because one of them dies. But, the ending is still hopeful and uplifting because the other protagonist was changed forever—in a positive way—by the romance, however briefly it lasted.

Although Sparks is often labeled as a romance novelist, if we use Angela James’s criterion, he shouldn’t be.

Based on an interview Sparks did with Writer’s Digest, it’d seem that he’d agree:

My books are very hard to pigeonhole because they’re not necessarily romance novels, they’re not necessarily family dramas, they’re not necessarily what’s typically regarded as Southern literature—so what are they?…It’s very difficult to pigeonhole what I write.

Point is: you can get away with a bittersweet ending if you’re writing a love story (which isn’t the same thing as a romance).

Noir (or neo-noir, if you prefer) is another genre that dictates the ending of your story.

In noir films and fiction, the world is painted as a dark and harsh place. Because happiness and hope are ruled out, you only have one option for your story ending.

happy- tragic

bittersweet

If you’re interested, below is a video that summarizes the characteristics of the noir genre:

Regardless of the genre of your story, perhaps you’d like to present the world as being harsh, hopeless, and unjust. This brings us to step #2…

Step #2: Reflect on the meaning of your story (i.e. its theme).

The theme of your story expresses your viewpoint on life. It’s a statement about how the world works.

Your story can say that the world is a harsh, hopeless, and unjust place. Or it can say the opposite.

It all depends on how you choose to end your novel or screenplay.

Think about a protagonist who, throughout a story, has tried to conquer his inner demons and become a better person. At the very end of the climax, he is faced with one last temptation.

The entire meaning of your story hinges on his decision.

If he succumbs to temptation at this final stage (a tragic, or perhaps, bittersweet ending), you’re saying it’s impossible for people to change. They cannot separate themselves from their weakness. This is a bleak worldview.

On the other hand, if you opt for a happy ending where he resists temptation (and gets to enjoy all the benefits that entails), you’re saying that people have the capacity for improvement, which is a more uplifting outlook.

Regardless, the meaning of your story is contained within the outcome of that final choice.

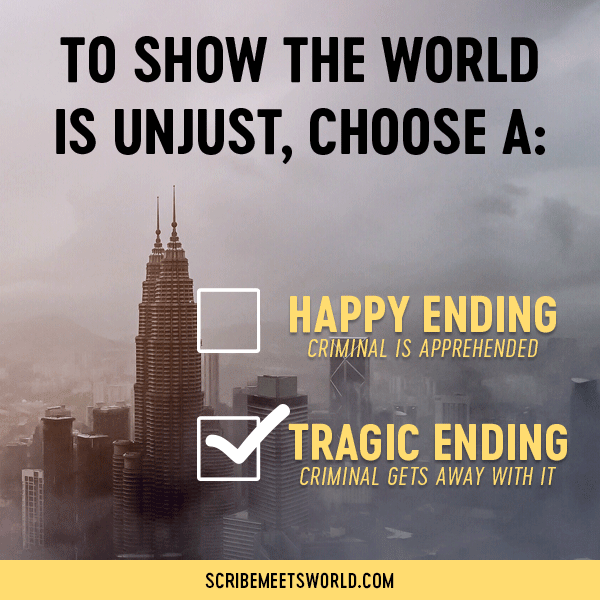

Stories in the mystery genre, by and large, end happily, i.e. the criminal is identified and apprehended at the end of the story.

However, if you believe the world is an unjust place—and you want your story to reflect that—then you should choose a tragic ending, where the criminal gets away with the crime.

Chinatown is an excellent case in point. Originally, Robert Towne chose a happy ending for his script. The murderer is killed. Evelyn Mulwray survives. She and Gittes kiss “as the sky opens up and rain comes pouring down…metaphorically washing away the sins of the characters.”

But director Roman Polanski chose to end the film quite differently. Evelyn dies. Her daughter is left in the custody of the murderer, who gets away scot-free. Below is a quote where Polanski explains his reasoning:

If it all ended with happy endings, we wouldn’t be sitting here talking about this film today. If you…feel…there’s a lot of injustice in our world, and you want to have people leaving [the] cinema with a feeling that they should do something about it in their lives, [then] if it’s all dealt for them by the filmmakers they just forget about it over dinner, and that’s it.

For the film to reflect Polanski’s view that the world is unjust, there was no other way to end the film. It had to end tragically. (Actually, for it to be billed as neo-noir, it had to end tragically, irrespective of Polanski’s worldview.)

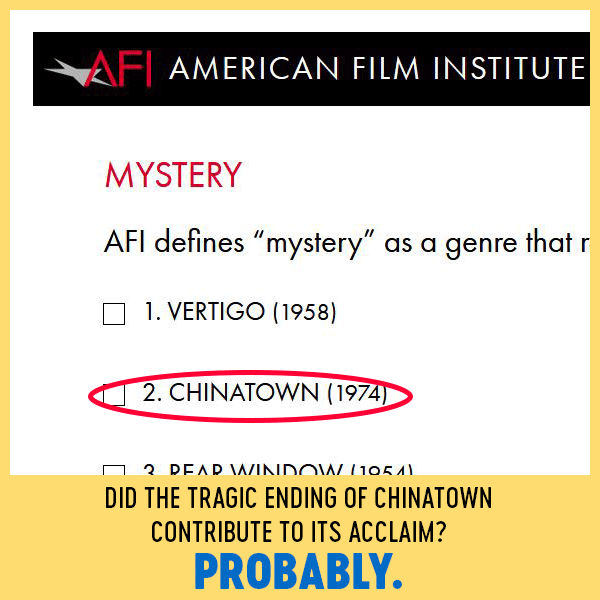

Chinatown is beloved by the critics. It won Towne an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay (and was nominated for several additional Oscars). Plus, it’s on the American Film Institute’s top 10 mysteries of all time. (In fact, it’s number two, behind Vertigo).

Despite its acclaim, Chinatown wasn’t that financially successful. According to Esquire magazine, Hollywood considers it a flop.

What do these details have to do with choosing an ending based on the meaning you want to convey at the end of your novel or screenplay?

Nothing. *wink*

I just want you to keep that in mind when we reach step #3. But before we get there, we have to finish our discussion of theme and your story’s ending.

To return to the topic of justice, happy endings tend to reflect the view that the world is a just place. However…

Happy endings aren’t synonymous with justice.

Let me explain.

Say, for example, you’re writing a story with a redemption plot. If your protagonist did something particularly egregious before he was redeemed, it wouldn’t seem quite right for him to enjoy a 100% happy ending.

For the scales of justice to be in balance, he has to pay for whatever sin he committed pre-atonement. Which means the most appropriate ending is likely bittersweet.

Bring It On illustrates this quite nicely. Torrance’s cheerleading squad has won multiple national championships by stealing routines from a neighboring school. Now that Torrance has discovered the truth, she’s determined to win victory based on merit. The film opts for a bittersweet ending, with her team coming in second place.

If filmmakers had opted for an unmitigated happy ending, her team would’ve come in first. But that wouldn’t feel quite just. After all, her team has earned years of glory at the expense of another. It only seems fair for that team to win nationals.

Moving on, consider a situation where an unsavory protagonist doesn’t get his comeuppance. Instead of getting punished, he gets everything he wanted.

Based on our definition—the protagonist achieves his goal—the story ends happily (for him at least). But because the protagonist is rewarded for trampling others on his rise to the top, it’s an ending that reeks of injustice.

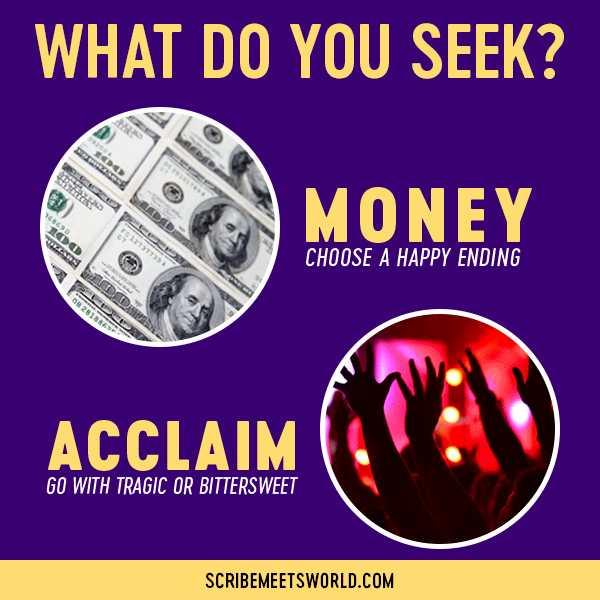

Step #3: Reflect on the impact you want this story to have on your writing career.

If you want to make money, then choose a happy ending.

As Michael Hauge observes in Writing Screenplays That Sell:

If given a choice, give your movie a happy ending, because, by and large, happy endings sell…Providing an audience with that emotional satisfaction, particularly if you are trying to launch your screenwriting career, increases your chances of getting work.

In How Not to Write a Screenplay, Denny Martin Flinn cautions screenwriters not to quote the famously tragic ending of Thelma & Louise to studio executives because tragic endings don’t make as much money.

Executives love to tell you how it [Thelma & Louise] would have made twice as much money if it had a happy ending.

If you look up the film, it made $45 million on a $16 million budget, which isn’t too shabby. Of course, in terms of commerciality, $90 million would’ve been even better.

But the film was compensated in other ways.

It received an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay (and was nominated for five additional Oscars).

If the movie had ended happily, do you think screenwriter Callie Khouri would’ve taken home a gold statuette?

Unlikely.

As Lindsay Doran pointed out in her talk “The Art of Storytelling” at the 2019 Austin Film festival, agents are “sophisticated” and “cool.” They want sophisticated and cool clients, and they want to make sophisticated and cool films.

It’s not unreasonable to assume that the voting members of the Academy (and other award-granting bodies) fit the same mold.

They want to reward films that are—like them—sophisticated and cool.

Alas, happiness, is anything but.

As more evidence, let us examine the Nicholl Fellowship, a prestigious screenwriting competition administered by the same group behind the Academy Awards.

Judges are asked to rate submitted screenplays on a range of criteria, one of which is this:

Are the themes of the story thought-provoking, across genres? Is the story “about something” that might spark discussion among friends?

Spark discussion.

That’s a telling phrase.

Happy endings are not exactly conversational fodder. (See Roman Polanski’s quote, above.)

So if you want to impress the judges of the Nicholl, you’re better off opting for an ending that’s either tragic or bittersweet.

As you can see, the residents of Tinseltown are at war with themselves.

They’ll push writers down the path of happy endings when they’re focused on money. But it’s the tragic and bittersweet endings that truly get them jazzed.

The same attitude appears to permeate the publishing industry as well.

We both know that literary fiction gets the most respect and the most awards—and literary fiction doesn’t tend to embrace the happy ending.

However, publishers who are thinking about the bottom line may prod authors of literary fiction to end their stories happily. According to author Heather Sharfeddin, who experienced this pressure firsthand, that’s one of the “biggest frustrations [that] literary authors face.”

The money-vs.-acclaim schism can also be found within the romance genre, whose signature feature, as previously mentioned, is the happy ending.

The genre’s well-known for its commercial success (according to one trade organization it’s a billion-dollar industry).

But it doesn’t get any respect.

As Salon.com columnist Noah Berlatsky put it, “critics don’t take it seriously…there is, in short, no romance canon.” The absence of a romance canon implies there isn’t “a group of experts who considers…the genre or medium in general, to be capable of greatness.”

In sum, if you want to make money as a writer, end your stories happily, as happy endings resonate the most with the general public.

But if you want to win over the critics and earn prestige and recognition, then tragic or bittersweet endings are better options.

Step #4: Reflect on whether your ending honors your story, your audience, or yourself.

Earlier, we examined how genre may dictate the ending of a novel or screenplay.

Sometimes, your story itself dictates how it will end.

It doesn’t matter whether your worldview is rosy or bleak. It doesn’t matter whether you’re seeking fortune or acclaim.

There’s only one legit option. And deep down inside, you know your story couldn’t end any other way.

Seven is a good example. A happy or bittersweet ending would’ve felt completely out of place. The film had to end tragically.

In other situations, the nature of your story doesn’t dictate the ending. In situations such as these, writers can reject the happy ending out of hand simply because they don’t like happy endings.

They consider happy endings to be:

- too commonplace, and want to rebel against the trend

- too unrealistic, and want to convey a more faithful depiction of life

Let’s take a closer look at the second item for a second. Somewhere down the line, you’re going to ask audiences to pay you (either with their money or—equally valuable to them—with their time). Because of this exchange, their needs should be taken into account at some stage.

Actually, I’m a proponent that your audience comes first, even before you. This is how I explained it in an interview for Kay DiBianca’s Craft of Writing series:

If you do a quick search for speechwriting tips, you’ll come across advice to think about the big takeaway that you want your audience to have.

If you do a quick search for copywriting tips, you’ll encounter similar advice. The sales pages with the highest conversions focus on the pain points of the customer, and how your product will solve them.

The way I see it, novel writing is no different. If you want readers to buy your books, you need to take their expectations into account at some point—if not when you’re writing, then at least afterward.

To sum up the above three paragraphs: audience before speaker; customer before product; reader before author.

By putting readers first, it doesn’t mean that you write by committee or cater to the lowest common denominator. It just means that before you send your story out into the world, you ask yourself, Okay this was fun for me…but will it be fun for my readers?

In her grammar guide It was the best of sentences, it was the worst of sentences., June Casagrande expresses this sentiment even more forcefully:

If you want to master the art of the sentence, you must first accept a somewhat unpleasant truth—something a lot of writers would rather deny: The Reader is king. You are his servant. You serve the Reader information. You serve the Reader entertainment…In each case, as a writer you’re working for the man (or the woman). Only by knowing your place can you do your job well.

Let’s apply this principle to happy endings. You may loathe them…but does the same hold true for your audience?

Why are they choosing to curl up with your novel on a rainy afternoon? Why are they leaving the comfort of their home to see the movie based on your screenplay at the theater?

Did they choose your story to be reminded about the way the world really is? Or did they choose your story to escape from that world?

If they are reading your novel or watching your movie to escape, and if you want to honor their needs (because they are paying for the privilege of this experience), then you have two choices:

- ignore your dislike of unrealistic endings, and opt for a happy ending

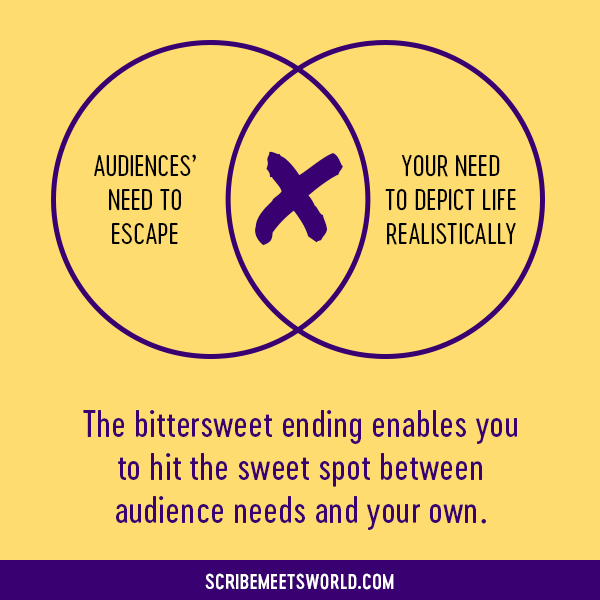

- make a compromise, and opt for a bittersweet ending

Let’s drill deeper into the bittersweet ending…

In a 100% happy ending, the protagonist does the right thing and is rewarded for it. He gets to enjoy the fruit of his labors.

In a bittersweet ending, the protagonist does the right thing, but wouldn’t live long enough to enjoy his victory.

In all likelihood, this is a realistic outcome (which honors your sensibility). At the same time, the ending isn’t a complete downer. It’s somehow infused with hope (which honors the members of your audience who seek out stories for escape).

An effective way to create that uplifting feeling and buoy the spirits of audiences is to, in some fashion, emphasize life.

Although your protagonist has died, subplot characters have survived their struggles. They at least have the opportunity to enjoy happiness. Alternatively, your protagonist himself will survive—but metaphorically. Unlike other men, he will not be forgotten. He will live on, as legend.

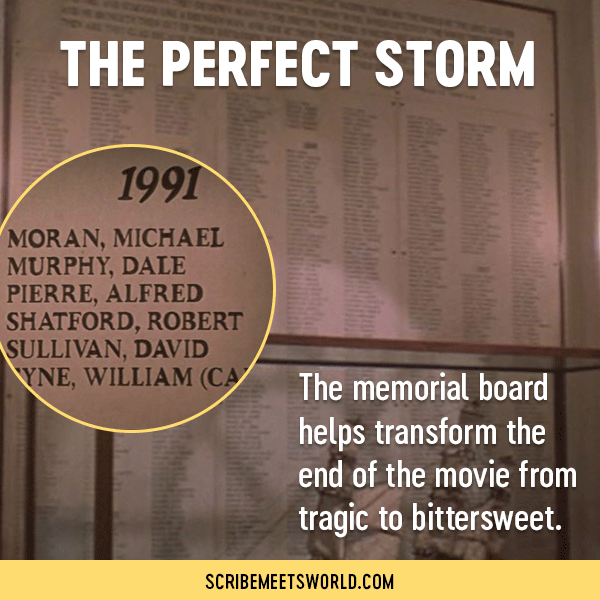

Think of The Perfect Storm. All six of the protagonist fishermen aboard the Andrea Gail perish, including the two men audiences have gotten the most attached to: Billy and Bobby.

Granted, The Perfect Storm is based on a true story. In real life, everyone aboard the Andrea Gail did die. To take creative license with that would perhaps be disrespectful to the source material.

Yet, despite this ending, the film isn’t a complete downer. (Notice also that it fared well at the box office.)

How did the film temper the sting of tragedy? Through three main ways.

First, subplot characters managed to survive the storm, even though the crew of the Andrea Gail did not.

Second, a voiceover from Billy indicates he lived well when he had the chance. Words from Bobby’s girlfriend describing him in a dream express a similar sentiment.

Both of these elements tinge the ending with hope.

Here’s Billy’s voiceover:

Fog’s just lifting. You throw off your bow line, throw off your stern. Head out the South Channel, past Rocky Neck and Tenpound Island. Past Niles Pond—where I skated as a kid.

Blow your airhorn, and throw a wave to the lighthouse keeper’s kid on Thatcher Island. Then the birds show up—blackbacks and herring gulls. Big dump ducks.

The sun hits you. You head north, open up to twelve—steaming now. The guys are busy, you’re in charge. And you know what?

You’re a goddamn swordboat captain. Is there anything better in the world?

And here’s Bobby’s girlfriend describing him in her dream:

I’ll be asleep, and then all of a sudden, there he is. That big smile. You know that smile.

And I say, “Hey, Bobby. Where you been?” But he won’t tell me.

He just smiles and says, “Remember, I’ll always love you, Christina. I love you now, and I’ll love you forever. There’s no good-bye. Only love.”

And then he’s gone. But he’s always happy when he goes, so I know he’s gotta be okay. Absolutely okay.

Finally, because the names of the fishermen have been added to a memorial board, audiences know these men won’t be forgotten.

Indeed, The Perfect Storm is a great model to emulate in order to craft a successful bittersweet ending.

Notice, though, to achieve a similar effect, you must take deliberate steps to infuse your ending with hope—creating subplot characters, voiceovers, memorials, etc. that maybe weren’t there before.

Going Further with Your Story Ending and Story Structure

After reading the tips in this article, you should know the overall nature of the resolution of your novel or screenplay.

But what should you put in it? And how long should it be? Find more tips for how to handle the resolution in:

- Chapter 14 of my writing guide Sizzling Story Outlines (which explains how to generate a loose or full outline for your story, step by step)

- Chapters 12 and 26 of my writing guide Sparkling Story Drafts (which’ll help you get your story ready to sell—faster)

- Module 3 of my online course Smarter Story Structure (more details, below)

To nail your story’s ending, you need to do more than get the resolution right. In addition, you have to ace your story’s climax. Learn how to do that with these resources:

- the climax of a story: a 101 guide with an overview of the basics (writing article)

- how to increase the tension at the climax—and make it a real nail-biter (writing article)

- Story Climax (a comprehensive writing guide that’ll teach you how to craft a story climax that’ll earn audiences’ enthusiastic seal of approval so you become a writer who’s in demand)

If you want to become better at all aspects of story structure (not just the climax and resolution):

- Download the Ultimate Story Structure Worksheet. (A free, 18-page worksheet that’ll help you plot your next screenplay or novel like a boss.)

- Read the writing guides in my Story Structure Essentials series. (In addition to crafting endings that exceed audience expectations, you’ll get a “deep dive” on how to set up your story for success and say good-bye to saggy middles.)

- Enroll in my online course Smarter Story Structure. (Distills years of studying why some stories are so gripping—while others are easy to walk away from—into 30 bite-sized lessons. Perfect if you want to learn how to wield story structure like a pro, in the shortest amount of time.)

Resolution door by Douglas Bagg; Plane wing by Brian Gaid; Bleak cityscape by Ishan@seefromthesky; Hands waving in the air by William White; Roller coaster by Mark Asthoff

Money by Ervins Strauhmanis